Kaspar Müller

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2022, Lightbulbs, e27 splitters, steel cord, electrical wiring, e27 ceramic lamp socket, 90 × 130 × 110 cm, 35 1/2 × 51 × 43 1/2 in

In Kaspar Müller’s practice seemingly familiar objects somehow appear as hieroglyphs. A cast of everyday, yet nonetheless strangely hermetic motifs reappear throughout his oeuvre like vanished memories. Recoded, recalcitrant, and on first glance sometimes stubbornly mute, past works have ranged from physically tangible sculpture to shadowy reproductions of images. Often working in recursive loops, Müller creates elusive installations that stage the fluctuations and transformation of the creative process between the space of the studio and the gallery. For Müller, this process is akin to archeology, yet the things he addresses aren’t hidden; we simply don’t pay attention to them. The moment that their latent qualities suddenly emerge and seem connected and appealing is an exciting moment, which, as Müller notes, is “prone to mystification.” Müller’s works examine the residues of different systems of production and value, honing in on the formal and associative qualities of everyday objects and goods. With his lamp sculptures, Müller engages with how industrial lighting, from its inception to the current day, functions as a means to create a mood or atmosphere through the expression of one’s aesthetic affinities. Müller’s interest in notions of craft and reproduction, and vintage and “fake vintage,” led him to bring together an exuberant yet discordant constellation of bulbs as a kind of mirror of the range of industrial production and contemporary taste.

Kaspar Müller (b. 1983, Schaffhausen) lives and works in Berlin and Zurich. During Art Basel Parcours 2023 Kaspar Müller showcased a large installation in Münsterplatz. Müller has had solo exhibitions at Atelier Amden, Vleeshal, Middelburg; Kunsthalle Bern; Museum im Bellpark, Kriens; Kunsthalle Zürich; and Circuit, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Lausanne. He has participated in group exhibitions at Fondazione Prada, Venice; Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno; Swiss Institute, New York; Istituto Svizzero di Roma, Rome; MAMCO, Geneva; and Aachener Kunstverein, Aachen, among other venues.

Art Basel Parcours 2023

Curated by Samuel Leuenberger

@ Art Basel and Prismago

On Basel's historic Münsterplatz a group of tall straw figures perform gestures like pointing, spreading out their arms as if to call for a stop, striding, crawling on all fours, and stretching, among others. Reminiscent of traditional ceremonies, folkloric customs, masks, and even scarecrows, they seem familiar and yet strange. Made entirely of natural, raw materials, the sculptures were built by hand as an ephemeral, site-specific, and temporary installation.

As a material, straw sparks myriad associations. Considered within the arc of Müller’s practice more broadly, which looks at the relationships between economy and craft, straw possesses a dual status as a practical commodity and nonfunctional decoration. Its uses as bedding, building materials, and animal forage are practically engrained our historical DNA, while also making it one of the earliest commodities. Not merely a by-product, straw remains highly in demand as part of agricultural economies and is still widely used today.

Recreating the human form in such an unceremonious and time-worn material emphasizes the feelings of empathy that people tend to have towards abstract, inanimate figures—a sort of reaffirmation of the condition humaine as both an abstract and existential term.

Müller’s sculptures spark curiosity and elicit interaction, not only through their familiar postures but also through their bodily empathy, and above all, their sculptural quality. These figures long to interact and play with the public in silent communication and complicity. They have an absorptive capacity: they soak up the space around them and, like the metaphorical straw man, divert your attention.

Installation view, Liquid Artist, Atelier Amden, Amden, 2023, photo by David Aebi

Kaspar Müller is showing a two-part work at the Amden Atelier, one part of it temporary, the other permanent. The work is an intervention conceived specially for this location and perceptions of it, and like earlier works by the same artist makes some surprising connections. Müller renders reality graspable in all sorts of ways — as an image or a paraphrase, say — and conveys it in a seemingly paradoxical manner.

This year, he is installing a solar-powered quartz watch in the gable of the barn. The first solar-powered watch, a Japanese model made by Seiko, came on the market in 1977. The Swiss watchmaking industry had no answer to this technological innovation at the time. The model that Müller uses in Amden, however, is not that first Seiko but a much later one, the Seiko Solar diver's watch dating from the year 2000, which has a distinctive yellow dial with an orange rim. The watch is too small for visitors to be able to tell the time from it; after all, this is just a wristwatch installed high up on the gable of a barn. But as the outcome of a technological leap, which viewed artistically looks like a little sun mounted onto the wall of an old, almost timeless building, it is also a resolutely poetic gesture that alludes to the specifics of the locale in many ways at once.

As cultural transformation processes and even more so the observable feedback phenomena to which they give rise play an important role in Müller's work, a solar-powered surveillance camera will transmit live images of the watch and its immediate surroundings for a limited period of time every day.

Fünf Figuren

Société, Berlin 2022

Société is pleased to announce Fünf Figuren, a solo show by the Swiss artist Kaspar Müller. The exhibition comprises a single installation in which five straw figures inhabit the gallery. Built at a scale slightly larger than life-sized, these blurry bodies enact what Müller calls “psychological behavioral blueprints.” Each figure performs a simple, archetypal gesture: one points at visitors, another gives a stop signal, while still others appear to purposefully stride through the space or crawl on all fours.

As a material, straw sparks myriad associations. Considered within the arc of Müller’s practice more broadly, which looks at the relationships between economy and craft, straw possesses a dual status as a practical commodity and nonfunctional decoration. Its uses as bedding, building materials, and animal forage are practically engrained in the European DNA, while also making it one of the earliest commodities. Straw continues to be used today for decorative ornamentation, yet historically possessed a quasi-supernatural function in its use to create talismans to ward against illness or ensure health and prosperity. Recreating the human form in such an unceremonious and time-worn material emphasizes the feelings of empathy that people tend to have towards abstract, inanimate figures—a sort of reaffirmation of similarity through difference, not unlike Müller’s ongoing work with his blown glass orbs. Yet while his orbs have a reflective quality that captures their surroundings, his straw figures have an absorptive capacity: they soak up the space around them and, like the metaphorical straw man, divert your attention.

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2022, Straw, fiberglass, wood, steel 200 × 110 × 100 cm, 78 1/2 × 43 1/2 × 39 1/2 in

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2022, Straw, fiberglass, wood, steel 200 × 80 × 115 cm, 78 1/2 × 31 1/2 × 45 1/2 in

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2022, Straw, fiberglass, wood, steel 195 × 210 × 65 cm, 77 × 82 1/2 × 25 1/2 in

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2022, Straw, fiberglass, wood, steel 195 × 90 × 65 cm, 77 × 35 1/2 × 25 1/2 in

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2022, Straw, fiberglass, wood, steel 175 × 70 × 70 cm, 69 × 27 1/2 × 27 1/2 in

Stop Painting

Fondazione Prada, Venice, 2021, curated by Peter Fischli

Installation view, Stop Painting, curated by Peter Fischli, Fondazione Prada, Venice, 2021

Catapults are usually used to fire projectiles using mechanical energy to accelerate the missile abruptly from a resting position. By incorporating this energy and making a catapult capable of hurling a bottle of wine at a wall to shatter it and create a colored stain, the work ironically alludes to iconoclasm and the abolition and destruction of sacred images. But as the power of the machine is relative, perhaps the potential for destruction that it evokes should include the anticipation of failure. Kaspar Müller collaborated with Iacopo Spini (formerly his student at ECAL – École cantonale d’art de Lausanne) on the design of the frame and the programming of the launch mechanism, which is digitally controlled.

Installation view, Stop Painting, curated by Peter Fischli, Fondazione Prada, Venice, 2021

Installation view, Stop Painting, curated by Peter Fischli, Fondazione Prada, Venice, 2021

Installation view, Stop Painting, curated by Peter Fischli, Fondazione Prada, Venice, 2021

"Mehr Licht!" - (Più luce!)

Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, 2021, curated by Rita Selvaggio

Installation view, "Mehr Licht!" - (Più luce!), Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, 2021

The concept of light has been a fundamental element of the history of art, as well as an indispensable means for the vision and transmission of colours in space, and ever since the 1960s has become an integral part of the expressive language of art. The journey made by light has very remote sources. It has passed through myth and metaphysics, theology and art, before being secularised in our everyday lives, trapped in our control and our practical activity. Becoming material of our objects and object of our work, it asks for a different perception of the world, a different bearing of the body, a much more fluid boundary between inside and outside.

And on this occasion Kaspar Müller confirms his practice of ‘bricolage’, transfiguring the codes of the design of furnishing accessories used for the lighting of interiors and subverting them through minimal variations, so as to invent other objects. The range of meanings commonly attributed to this kind of element works with images, icons and groups of symbols to produce a single system that expands in time and space to suggest alternative scenarios of loss and subsequent recovery of energy. For -“Mehr Licht!”- Kaspar Müller has specifically conceived Tree of lights (2021), a work that moves between sculpture, design and art in a functional context.

Installation view, "Mehr Licht!" - (Più luce!), Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, 2021

Installation view, "Mehr Licht!" - (Più luce!), Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, 2021

Installation view, "Mehr Licht!" - (Più luce!), Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno, 2021

Installation view, In and Out, Galeria Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2020

For In and Out Kaspar stages a hermetically sealed, stage-like space that appears completely permeable. The sculptural objects; the toilet paper paintings, the glass orbs, the chandelier and the 3D print of a wine catapult remind Kaspar of props or stage sets, the drawings of figures. Promising an ostensible festivity, the exhibition is arranged as if it were approaching a punch line.

In their industrially standardized appearance, the motifs of the exhibition appear as familiar, as they appear redundant to the viewer. Sentimentality can not unfold here because even the transience of the motifs and objects appears preserved and controlled. Thus, the exhibition is more maintenance than memento mori its works remain superficial and inaccessible. No narrative that connects the objects in the exhibition, so nostalgia cannot arise, because nostalgia lives in narrative. Maintenance, from the French “main tenant”, could be understood here as the need for a material connection, as a form of reconfirmation.

Installation view, In and Out, Galeria Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2020

Installation view, In and Out, Galeria Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2020

Installation view, In and Out, Galeria Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2020

Installation view, In and Out, Galeria Francesca Pia, Zurich, 2020

Mandala

Société, Berlin 2020

More or less immediately I had to think of a painting by Henry Wabel, “Stilleben mit Kinderzeichnung.“ I remembered seeing this painting around 1969 in the collection of the Museum in my hometown. I was 18 or 19 years old at the time, and starting to think more and look more and more at art. Conceptual art was a new and fresh thing. So it was through the eyes of that momentum that I saw this painting – the idea of that painting as a conceptual art work. I was enthusiastic about it, about the thoughts I was seeing in it. Everything was there – a kind of appropriation art “avant la lettre,“ a readymade inside a painting, the question of authorship and on top of it the questionable phantom idea of the authentic. I was, as they say, “illuminated“ by this painting.

Time passed, I forgot about the painting and illumination was turning back into a dim bulb. I had to go back and do some research because I couldn’t even remember the name of the artist. During this little research, I stumbled across another painting, done a long time ago, like 500 years ago, by Giovanni Francesco Caroto.

Dear Kaspar, I am sure you will like that painting as much as I do.

Installation view, Mandala, Société, Berlin, 2020

One day, while spending an extended period of time together at home earlier this year, Kaspar Müller’s six-year-old daughter Katharina surprised him with a painting on a single square of white 3-ply toilet paper imprinted with a repeating pattern of butterflies and flowers. Perhaps it was the slowed down pace of this intimate time, or simply the innocence and curiosity of a child’s mind, but his daughter had infused new life into a quotidian element of industrial design. Using an array of oil crayons, she meticulously colored in the paper’s indented patterns, unlocking a crisp and bold design through a delicate, yet decisive intervention. What ensued was an inter-generational exchange through the medium of one of the most banal household staples.

Müller’s new paintings emerged from the positivity and beauty that his daughter’s own paintings found in a product that is ubiquitous, empty, and profane—and his work maintains the sublime fluffiness and luminosity of the original. He performatively re-enacted her works on a grand scale through various layers of technical intervention. The large-scale prints not only emphasized the embellished pattern, but also the object-like quality of the paper sheet, including at times tattered or lightly torn edges. Müller then performed another layer of intervention by painting atop the image of his daughter’s flowers with the same colors. Such a gesture brings about a moment where oil and digital patina meet in the fusion of an adult and a child’s approach to making.

In Kaspar Müller’s practice seemingly familiar objects somehow appear as hieroglyphs. A cast of everyday, yet nonetheless strangely hermetic motifs reappear throughout his oeuvre like vanished memories. Recoded, recalcitrant, and on first glance sometimes stubbornly mute, past works have ranged from physically tangible sculpture to shadowy reproductions of images. These paintings con- tinue Müller‘s practice of working in recursive loops. By combining elements of pop and daily life, the works in Mandala hone in on the formal qualities of one of the most common objects used for personal care—transforming the industrial space of decorative pattern as a contemplative and expressive zone.

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Kaspar Müller, Untitled, 2020, UV cured ink and Sennelier oil pastel on canvas, 210 × 160 × 3 cm

Rendering of service in the pitch of the bruise

der TANK, Institut Kunst HGK FHNW, Basel, 2019, curated by Roman Kurzmeyer

Installation view, Rendering of service in the pitch of the bruise, der TANK, Institut Kunst HGK FHNW, Basel, 2019

The FHNW Academy of Art and Design views the Campus of the Arts, where der TANK exhibition space is located, as a cultural and creative cluster that is intended to change constantly and offer optimal conditions for various stakeholders. In addition to the university with its approximately 1,000 students, this newly developed urban agglomeration includes the House of Electronic Arts (HeK), the Library of Design and the poster collection of the School of Design, the Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron Cabinet, and small private companies in the creative industries, as well as apartments and office spaces. Located near the university are the Merian Gardens and the Schaulager museum. So far, on the Campus of the Arts there are no grocery stores, no bar, no department store, no daycare center, no post office, and no medical center, because the campus focuses on design, art, and media in terms of both content and space.

The glass-fronted exhibition space is the antithesis of the White Cube. It is public space. The outside world is not shut out. Glass walls steer one’s gaze toward the outside, but also mean that passers-by can look in. The exhibition by Kaspar Müller uses TANK as a glass showcase to advance the cluster. He has brought a post office and a medical center to the campus. It is a bluff. The services are housed in identical, industrially prefabricated, small wooden sheds for allotment gardens that the artist bought from a hardware store and transformed into brightly illuminated backdrops. The post office facade is gorse yellow, that of the doctor’s office is zinc white, and each are furnished with a highly visible emblem. His new film Rendering of service in the pitch of the bruise (2019) will be shown on each flat screen in the two tool sheds, which are big enough for three or four people. We watch Timothy Lee Standring in the lead role playing three characters: a doctor, a sick postal employee, and a cook preparing a dinner for a nuclear family.

In 1996, the artist and exhibition curator Peter Weibel—in the style of the American cultural critic Gilbert Seldes—referred to postindustrial society as a new “mainland” that longed for an altered concept of culture and would create new forms of work and mediation formats in art. The “universal expansion of culture (everything becomes art, everyone becomes an artist) and the universal transformation of everything into commodities, even artworks” are part of the “cultural logic of late capitalism.” Economization has long included areas such as education, health, communication, and transport, namely providing people with essential (cultural) goods and services. Kaspar Müller’s film brings us face to face with this situation and postindustrial society’s concept of labor. He discusses the consequences of the total economization of society and addresses precarious working conditions.

Work has only been considered as something positive since the nineteenth century. It was the French philosopher Jacques Rancière who reminded us that art played a significant role in this revaluation, because it unites “the traditionally opposing concepts of manufacturing activity and visibility in one idea.” Rendering of service in the pitch of the bruiseis an exhibition that stimulates discussion about this positive concept of labor, which Thomas Hirschhorn also refers to in his work for example, in a place where many young people desire a life as an artist.

Roman Kurzmeyer

Installation view, Rendering of service in the pitch of the bruise, der TANK, Institut Kunst HGK FHNW, Basel, 2019

Installation view, Rendering of service in the pitch of the bruise, der TANK, Institut Kunst HGK FHNW, Basel, 2019

Why always me?

Société, Berlin 2019

Installation view, Why always me?, Société, Berlin, 2020

Kaspar just called me to say that while he was printing a draft of this text to edit, one of his students asked what he was doing. He explained and she replied, “Photography makes me sick.”

The genres within photography have fragmented into tiny shards, of which we are acutely aware even if we don’t name them. We have developed a nuanced ability to read images, one that runs parallel to aesthetics. It considers what an image is trying to communicate, through what strategies, and assesses its overall success in situ. The photograph has made itself too available to us. We take them for granted and are entirely dependent on them. At the same time, we have let ourselves become so immersed in this sea of images that we begin to mistake them – their volume in particular – for a means of understanding.

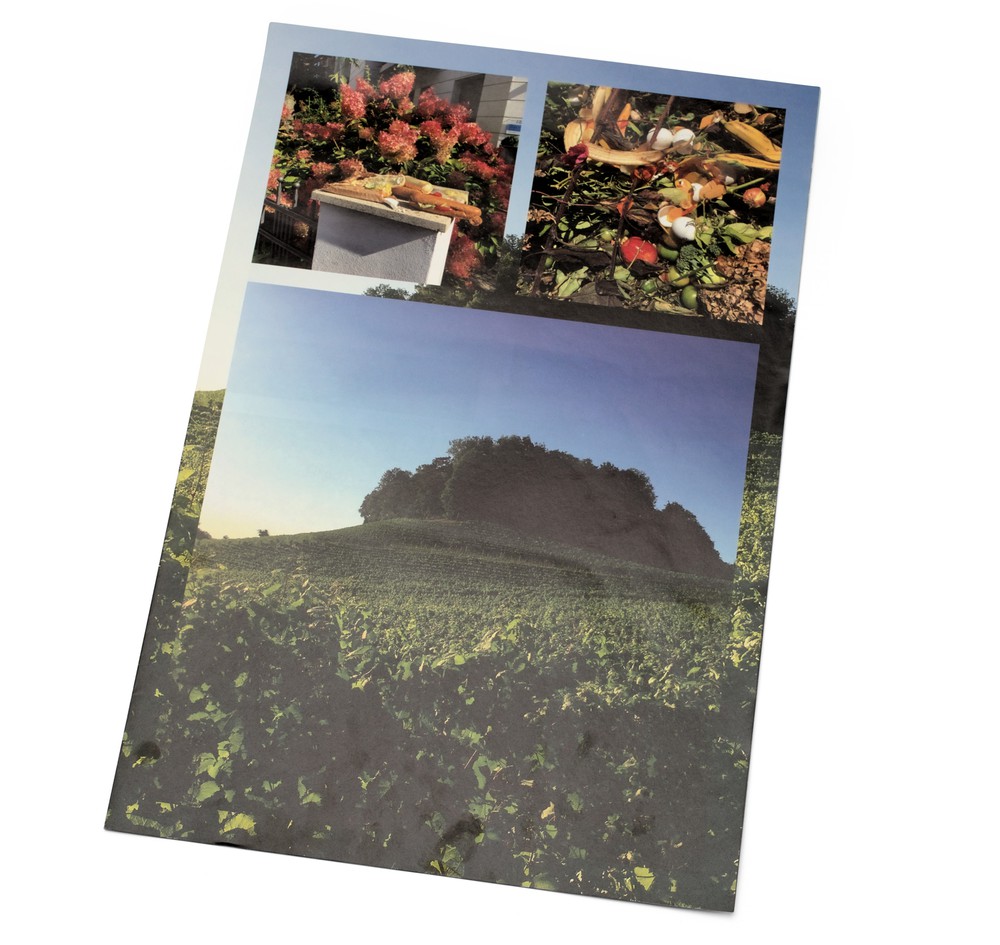

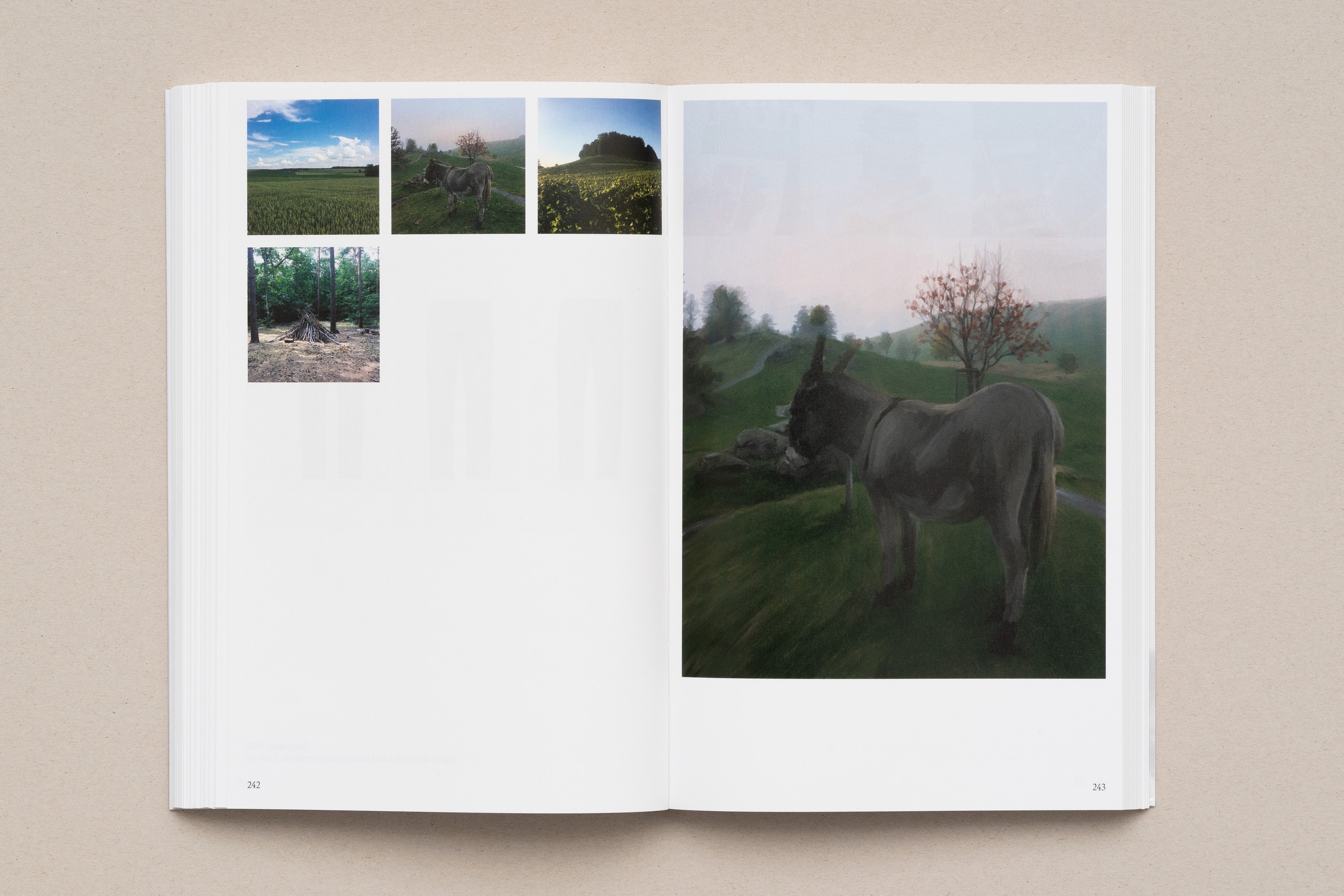

In an earlier text on Müller’s work I wrote that he “undermines the conventions of the reception of art as it has come to be today: a hydra of communication, promotion, advertising and social posturing. He still exists within this system – it’s more or less inescapable – but many of his actions as an artist try to peel the curtains back a bit.” The photographs shown here, taken over the past decade, offer up an illustration of the system as it has become intertwined with an individual’s life. They open a window into Müller’s travels (many of which were sponsored by those supporting his work as an artist), his experimentations in the studio, his exhibitions and participation in art fairs, and his personal life – including portraits of his son and his family’s cat. From the description, one could just as easily be talking about his Instagram account. Their collective title – “Why Always Me?” – is like a twinned admission of the self-involvement of being an artist and an attempt at absolution.

Photography in the context of an art exhibition exists outside of photography as we normally experience it in our day to day lives. It’s an anachronistic return, a suspension of reality, where we as an audience are given the privilege of contemplating an image for a little longer than usual and with a different type of attention than scrolling through photos on social media. The gallery as a secular and insulated place of contemplation is a nice little truism we act out.

Müller’s photographs push this privilege fallacy over the line. Some are suspiciously aestheticized; others embody advertising clichés too happily. There are views of neatly tilled fields, oranges dangling from a tree dappled in sunlight, a child wearing a classic rain ensemble stomping in puddles, and a timid calf. They are images that beg to be ‘liked.’ These types of photos are punctuated by documentation of Müller’s artworks, which rupture the serene fabric of sunlit charm with fluorescent directness. Many of the artworks pictured are utilitarian things turned absurd, and therefore less useful: a shelf covered in feathers, a ham-fistedly painted chair, and (in a lush crossover) dozens of novelty light bulbs have been cobbled into ceiling fixtures and installed in an ornate room with views of palm trees from the windows. It is not uncommon for artists to populate their Instagram accounts with photos of their work; it is uncommon to elevate documentation of old artworks into artworks themselves and install them in a gallery. And so both factions in this group of images skew closer to the technologically dependent, voluminous, contemporary way of consuming photographs – even down to the square format of some – forcing us to grapple with this distribution/consumption phenomenon along with the more familiar questions that come with evaluating an artwork.

Perhaps this is why Müller has sat on some of these photos for seven or eight years. Shown at another time or in a different context they would not have effected the same response. Müller’s work often functions best when it’s at the cusp of dissolving into innocuousness. These images show an array of the type of photos that accumulate around a person and purport to amount to a kind of behind the scenes of a creative life. It is only recently that artists (and, of course, pretty much everyone else with a cell phone) began curating pictures into a publicly shared exhibition-persona. The prevalence of the photo diary is – one would assume – at an all time high. The space of everyday life is supersaturated with images, and as more and more ‘content creators’ crop up, certain ideals about artists are beginning to bristle up against normal, everyday existence. People spend hours per week wading through this content, most of it meaningless. I personally am so addicted to looking at other peoples’ photos that I had to enable a feature on my phone that locks me out of the apps after a specified amount of time each day. I never really thought of this activity as art viewing.

By masquerading as the omnipresent, Müller handicaps himself. He seems to defang his work, asking it to chase familiarity and digestibility. In doing so he reveals how these endearing qualities can often mislead us. We know that photographs can be manipulated, but we frequently ignore the ways in which photographs manipulate us. They are a source of anxiety and, paradoxically, a panacea. In connecting us to the world, they allow us to reassure ourselves that we understand it. It’s easy to get the impression that we know a person or a place by looking at pictures. Somehow it has become easier to forget the fact that whoever is pressing the shutter button can easily leave something outside of the frame.

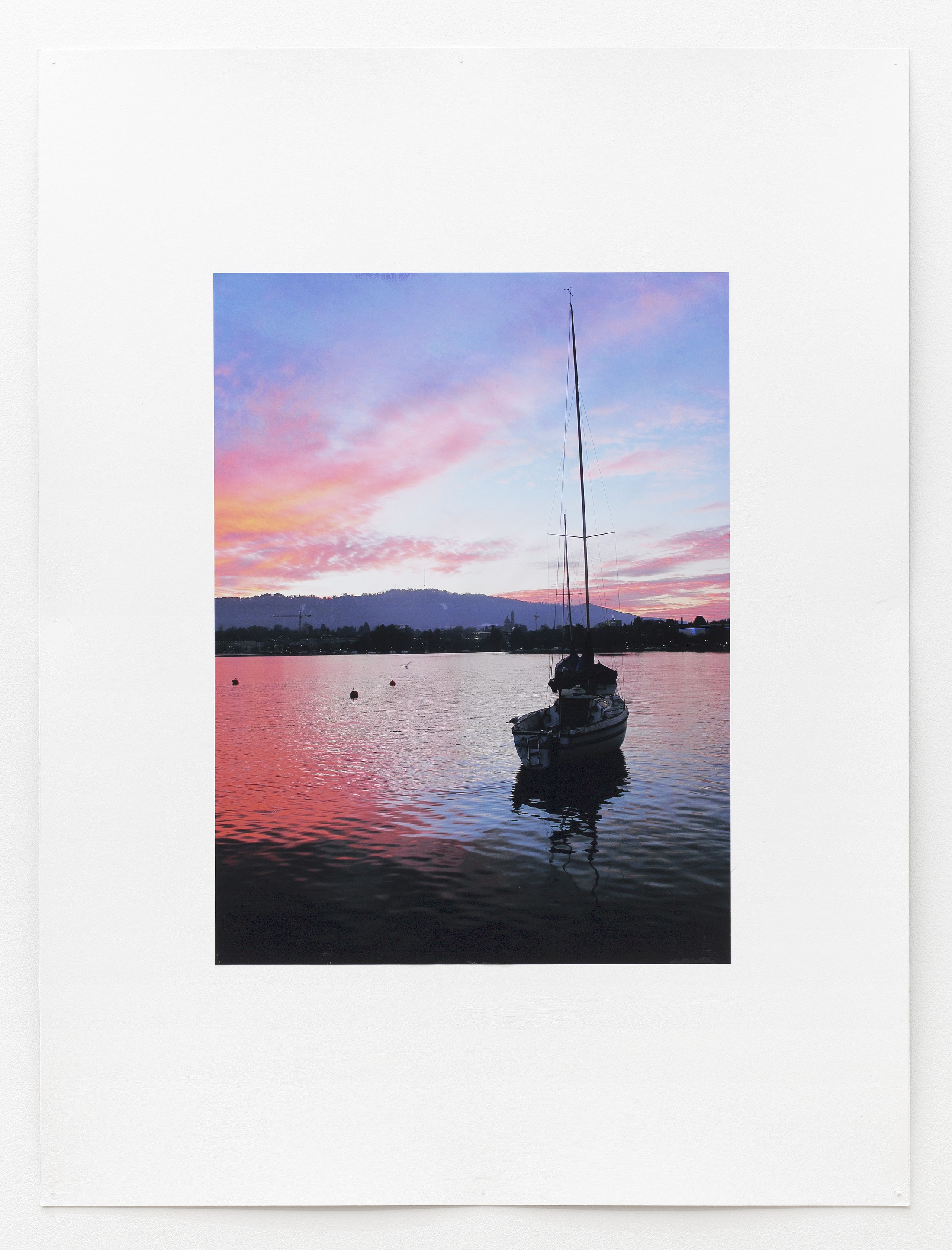

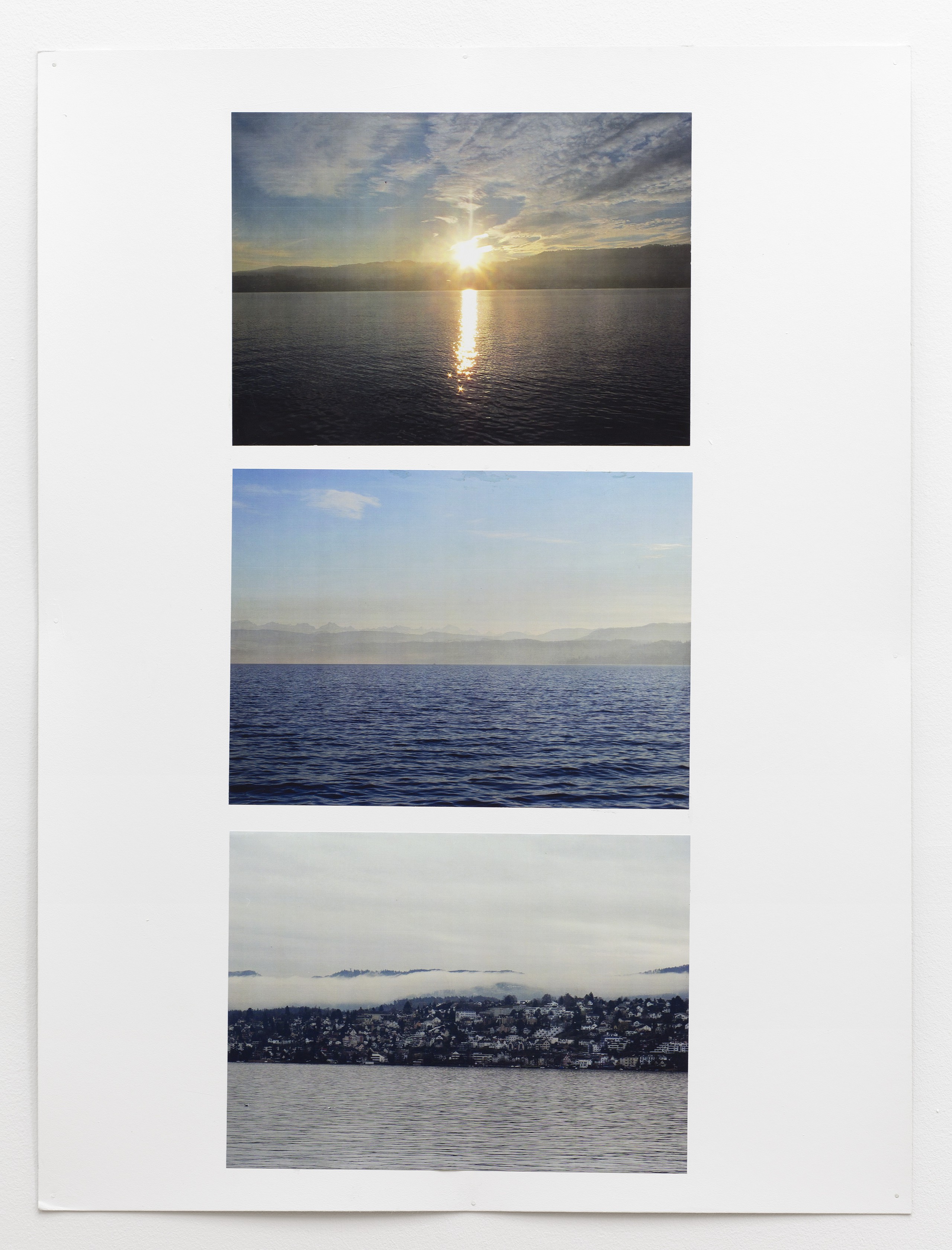

Nearly all of Müller’s photos leave something out, and somehow this is the point. When talking about his earlier series of photos of Lake Zürich, Schätze der Erinnerung, Müller said, “It was as important to hide some subjects as it was to point some out.” The resulting pictures – taken over the course of a year using different cameras – ape the style of postcards while retaining a degree of amateurism. They achieve the sort of blankness that one can project into. Doing this required Müller to keep a lot out of the frame. With the singular focus of an advertisement, the only subject Müller pointed out was Lake Zürich. It took a willing audience to parse through all of that subject’s complex meanings: environmentalism, politics, abundance and scarcity, capitalism and worth, and not least of all, leisure. The same can be said of these photographs. Despite a diversity of subjects, Müller has nonetheless whittled things down. His chosen subjects generally sit at the center of the frame. They idealize and document idealization. Many focus on the relationship between humanity and nature, illustrating our desire to cultivate, domesticate, name and take ownership. Like the Lake Zürich photos, there is something unsettling about how nice they all are – the hidden subjects begin to creep in from the edges. Some depict the impulse to build, be it a simple lean-to or a hollow, faux Greek colonnade; others picture the waste that trails in our wake. A collection of eviscerated baguettes left to fester on a fence pylon begins to feel like a candy-hued update on Dutch still life. Then, I remember that vanitas paintings are all packed with symbols of fleeting pleasure and the eventuality of death. This sentiment permeates and I begin to wonder, is anxiety our most common emotion?

Installation view, Why always me?, Société, Berlin, 2020

Installation view, Why always me?, Société, Berlin, 2020

PUBLICATION

Installation view, Allegiance & Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 2019

Following Müller’s strategy to non-hierarchically combine originals and copies, this text consists of fragments copied and pasted from other texts about his work. The title of the show, Allegiance & Oblivion, is taken from his first solo exhibition at Galleria Federico Vavassori. It is meant to suggest a dialectical friction between a loyalty to the codes of cultures as of art (allegiance as devotion) and a reality of things, which we are not able to grasp and rather constantly fail to achieve (oblivion, as amnesia, but also nothingness, silence).

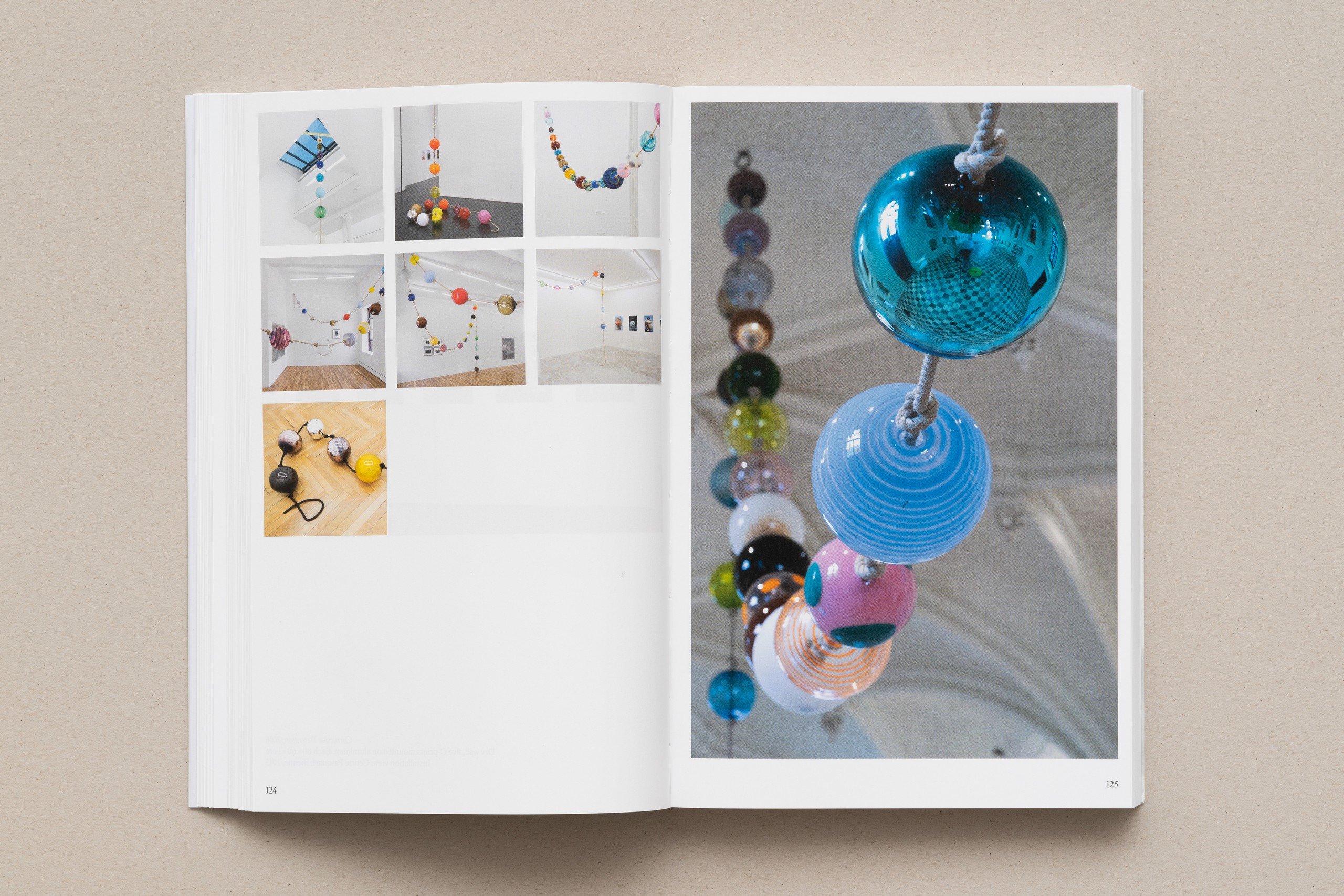

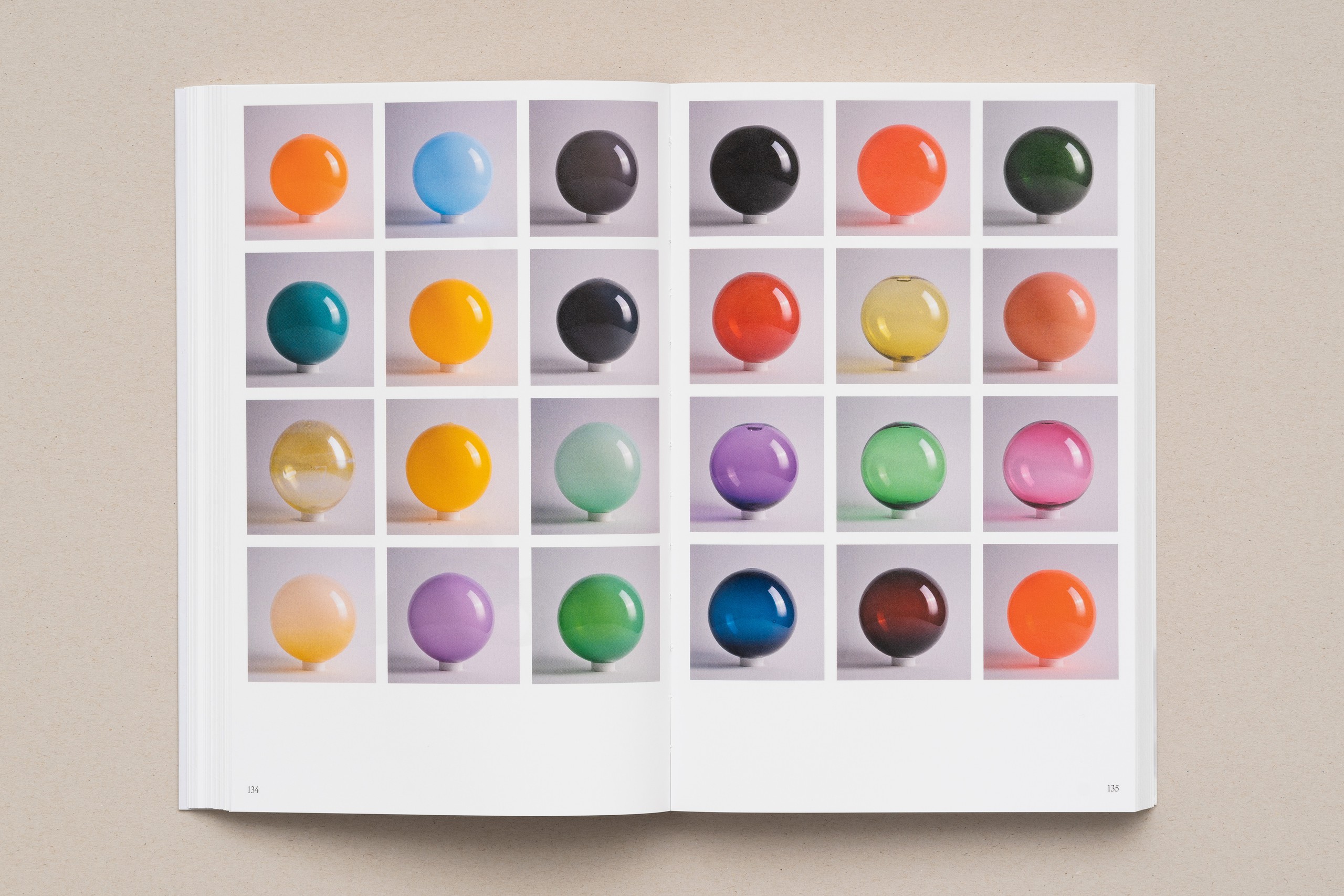

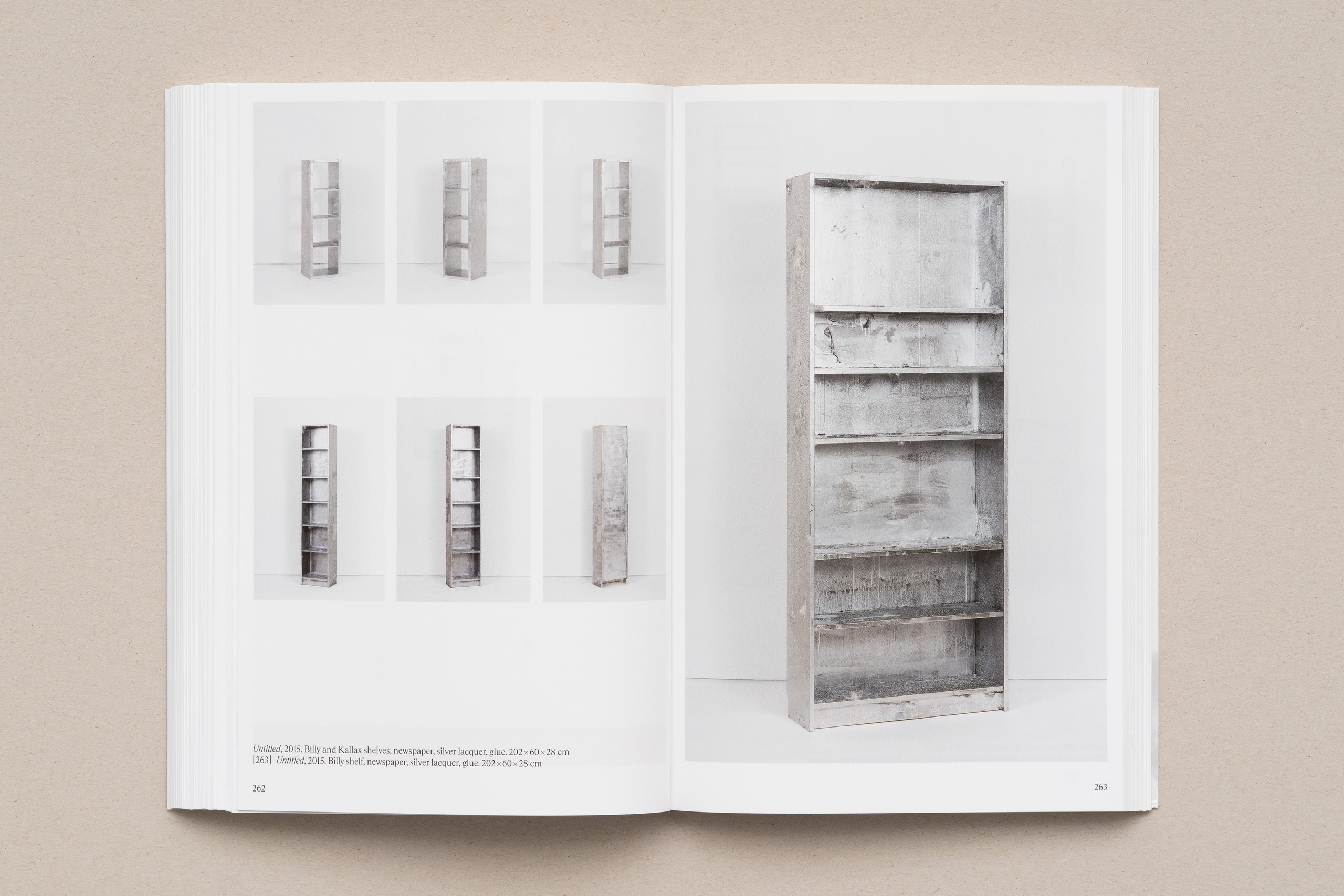

A mode of Müller’s process is an accumulation of objects and images, which are submitted to the viewer beyond any cataloging or order, but only and joyfully in their variety and heterogeneity. Works which develop into series—think of furniture such as wardrobes, bookcases, and trunks—coexist with works that include series of objects and/or images—think of the crowns of blown glass bubbles that are, perhaps, Müller’s most iconic work. In these works, a metonymic tension between the part and the whole results in a collection of individualities that the viewer can only experience in two ways: through the juxtaposition between the parts, hence the assertive exercise of comparing the quality of each glass orb; or the awareness of one’s own otherness in relation to the work, an entity alien to the viewer. These works are inclusive and engaging, but at the same they hint at the solitude of both work and viewer, both subjects doomed to wander among a multiplicity of status and contexts.

Installation view, Allegiance & Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 2019

Installation view, Allegiance & Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 2019

Installation view, Allegiance & Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 2019

Installation view, Allegiance & Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 2019

Installation view, Allegiance & Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 2019

Installation view, Allegiance & Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 2019

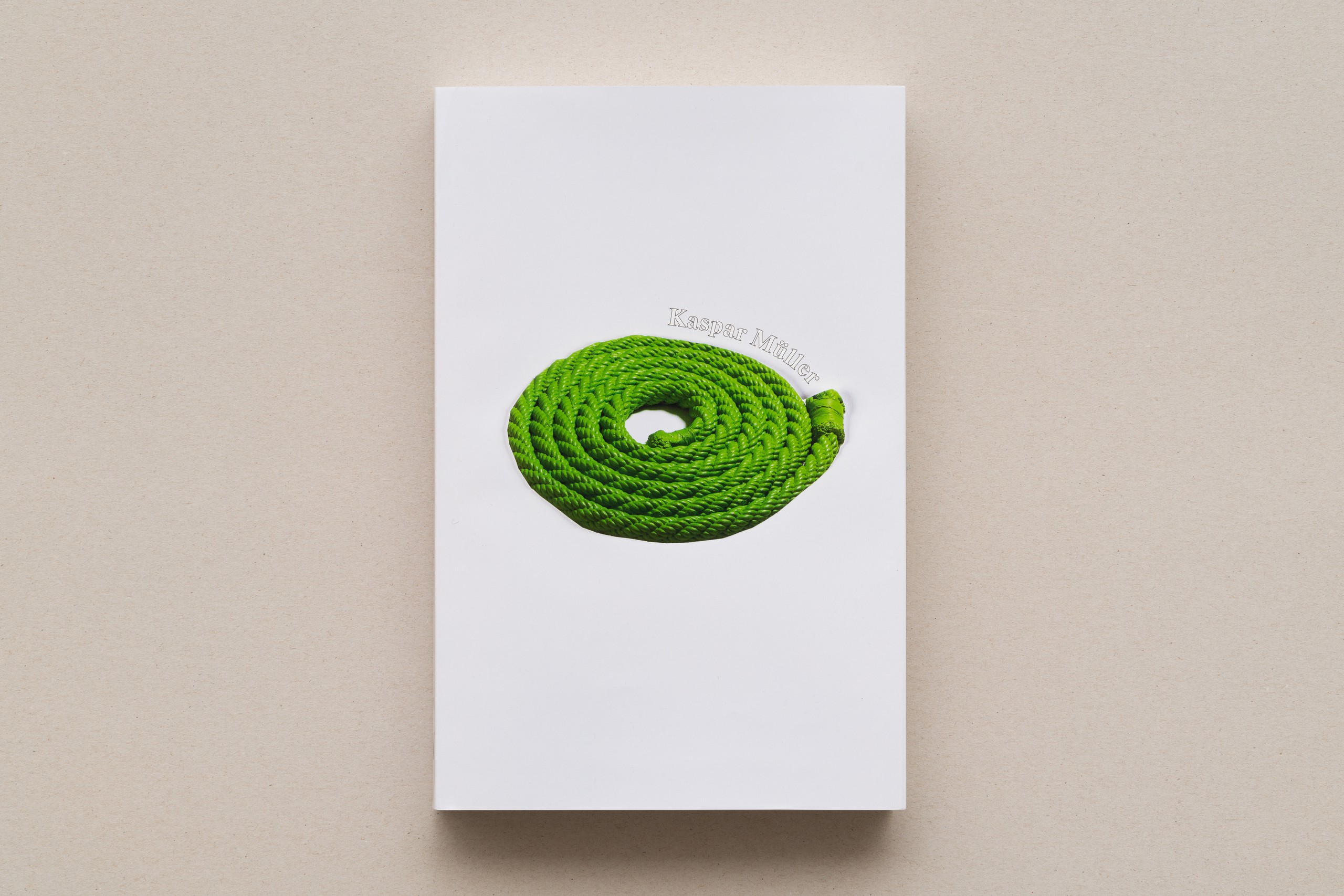

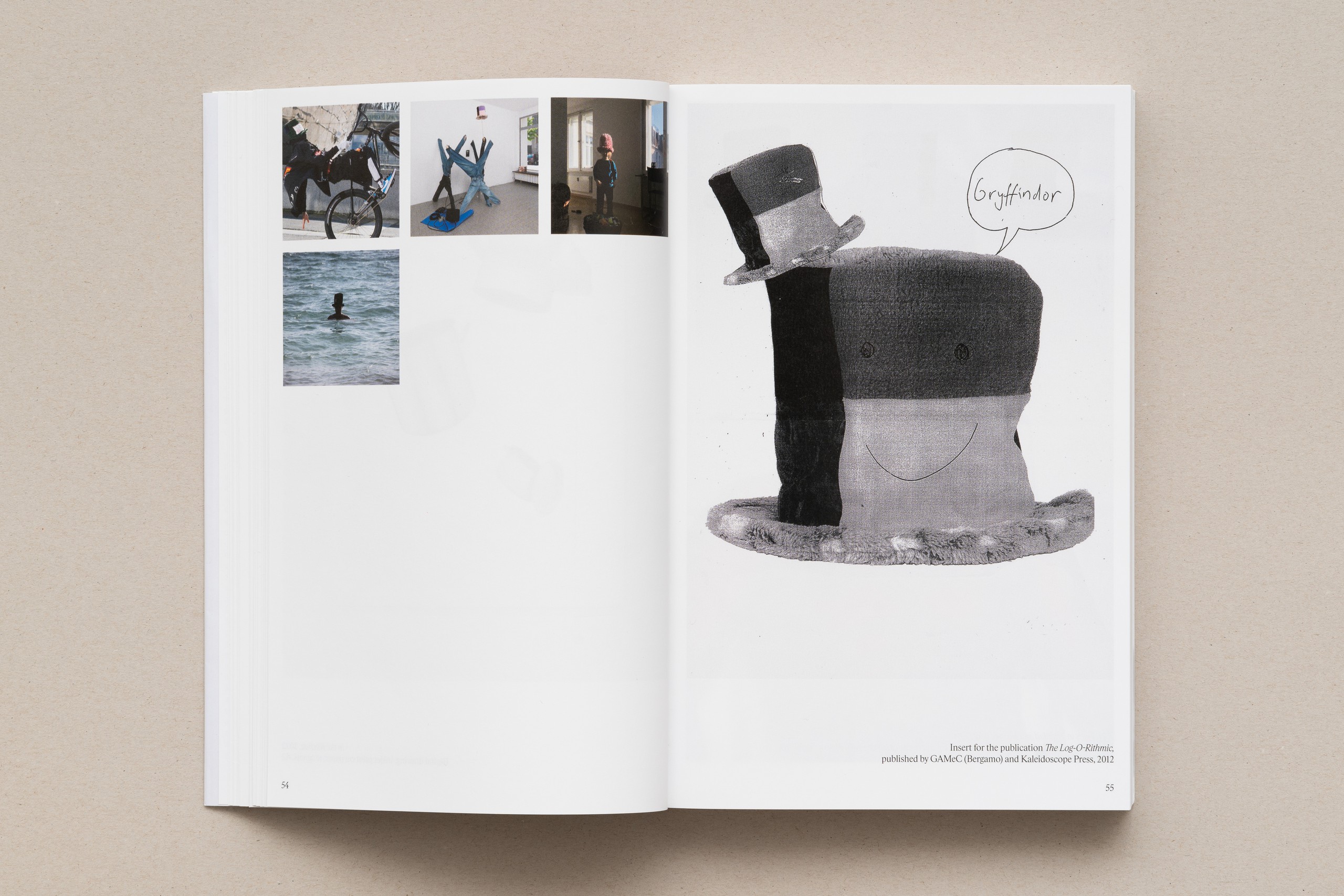

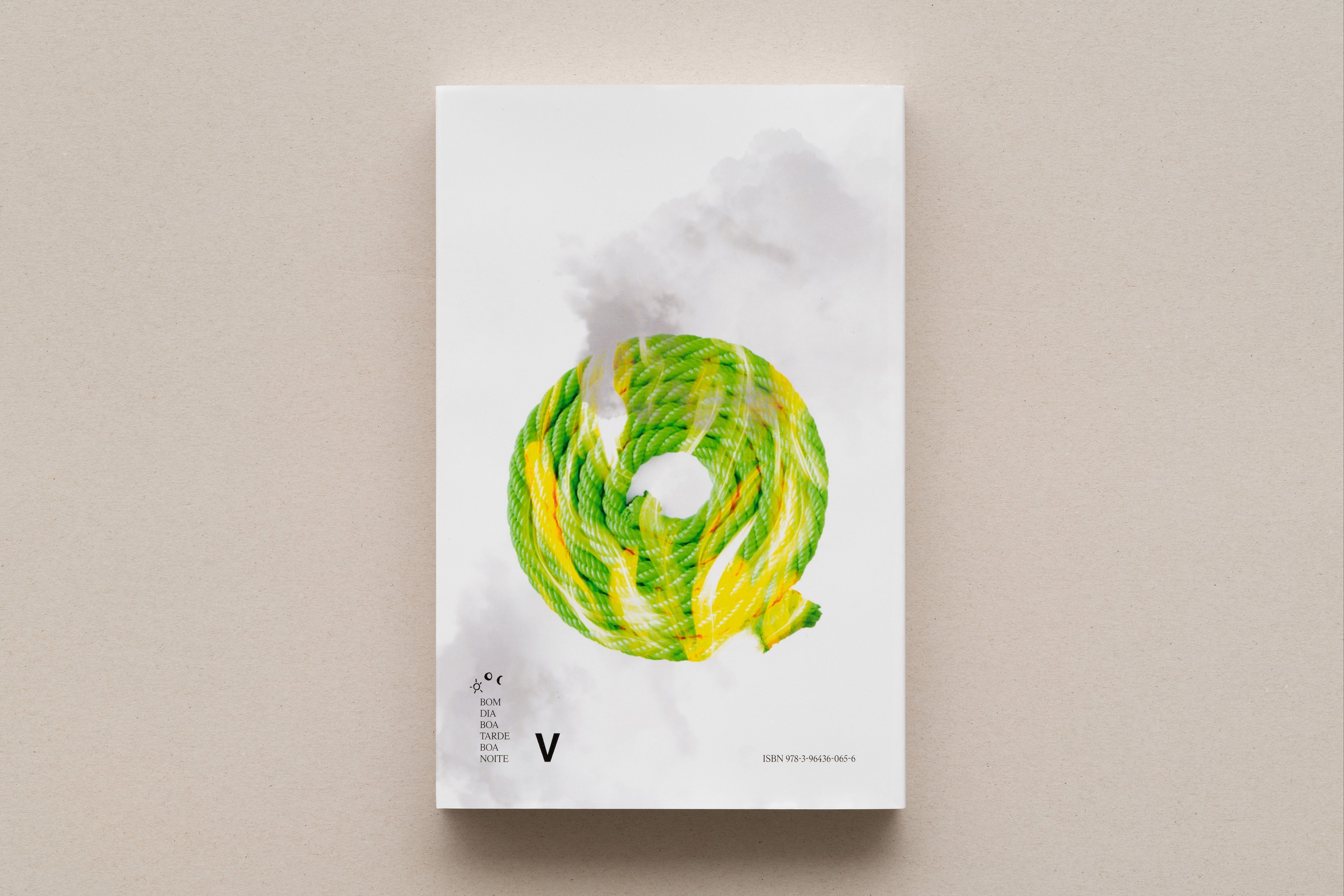

This book was published in conjunction with the exhibition Kaspar Müller, Allegiance & Oblivion at Vleeshal in 2019. It provides a profound insight into Kaspar Müller’s multi-layered art practice of the last ten years, which oscillates between sculpture, installation, video, photography, painting, and drawing. Much of the conceptually driven work of Müller is enveloped in irony and black humor, often conceived to comment on the creative process itself and on the influence of capitalist economy on life and society. Müller’s work is usually presented as an accumulation of objects and images beyond any cataloging or order but only and joyfully in their variety and heterogeneity. Corresponding with this way of working, the selection of images in the book is arranged in loose and playful associations, without fixed categories or set chronology. Exhibition views are combined with photographs, video stills, and images of works. The design of the book encourages you to browse through its image section in different ways. Besides the usual movement from cover to cover, contributions by Arthur Fink, Fabrice Stroun, and Audrey Cottin provide other options to navigate through the book, as each essay or interview mentions its own selection of works in a different order.

Editor: Roos Gortzak, Vleeshal

Texts: Audrey Cottin, Arthur Fink, Roos Gortzak, Fabrice Stroun

Designer: Marietta Eugster with Fabian Fretz

Co-publisher: Vleeshal

Artist: Kasper Müller

Category: Artist books, Kataloge

Art Basel Miami Beach, 2016

Installation view, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2016

I wouldn’t go so far as to say that Kaspar makes a secret of the way he produces these works, but there’s some mystery to them. To their obviousness, among other things. Both the furniture works and the glass ball works are almost painfully obvious gestures. The one, seemingly endless iterations for no good reason. The other, seemingly endless redundancy for no particularly good reason. In each case: endless, exasperating possibilities. I’m going to be frank, and it’s going to seem inopportune, but you could even say we’re facing as many possibilities as needs allow. As many colorful iPhone cases as you’ll find for sale on Canal Street, as many plastic Happy Meal toys as McDonald’s will produce, as many vintage clothing stores as now span the globe. Then again, my point exactly: How many do we actually need? What is need after all?

Need might be demand, and not in the sense of basic needs, but in the sense of a society, its industry, and the socioeconomic interests that get communicated to us publicly, privately, and in any digital space with an ad-based revenue model. Essentially we’re talking about the need for consumers to consume. For industry to grow and tech to grow with it and for consumers to continue their habit of being subjects, semi-public subjects, in contemporary society via semi-public consumption.

The glass ball works maybe not so much, but the furniture works are the product of Kaspar being a consumer. He goes through the motions of your everyday, somewhat design-inclined, bourgeois bohemian furniture shopper. He made an at least half-assed investment of time and energy into getting a sense for what people like or liked and buy or bought, for what genres are out there, and how he might be able to get a hold of certain pieces. An air mattress — Walmart, duh. One Spaghetti chair by Belotti, a Saarinen chair for Knoll, an Eames table. This metallic green fiberglass throne – omg one of the founders of the Memphis group – did you see Bowie’s Ettore Sottsass stuff for sale? He knew. And a shabby chic white wooden chair. It just screams ‘studio’. Or ‘Berlin’. Or ‘Airbnb’. Anyway, anything other than ‘corporate campus’.

Installation view, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2016

Installation view, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2016

Installation view, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2016

jmseradzfghdsjkfhbycmxcfnbkladshj

Société, Berlin 2016

Installation view, jmseradzfghdsjkfhbycmxcfnbkladshj, Société, Berlin, 2016

Summer 2016, email: I was really in a positive mood.

In “jmseradzfghdsjkfhbycmxcfnbkladshj”, his third one-person exhibition at Societé, Kaspar Müller presents painted, printed and assembled materials.

It took one whole year, this fucked up, fantastic year, to make these works. How do you look at a world like this? Through flags maybe. The mood is rotten, levelled by material density. Two or three colors, on par with each other, too much data. There is clearly a distance, the length of projection, which al- lows to place pleasure next to melancholia.

Over summer the artist moves his studio and consequently reduces his work space to a fifth of its volume. The clothmaker who sublets the new place leaves a sewing machine, a loom, and some sewing patterns hanging on the wall. The most evident things easily become the most inadequate ones. Football, Brexit or smoking weed; it’s just paint on canvas, under the rule of the squeegee.

It isn’t really preferable to read the signs of our time as styles and vice versa, it isn’t attractive to read at all. The signs, which signify knowledge and heritage, are eliminated. Books and flags. Something to say: the plumage of collectivity.

There is an inclination to buy canvas. Burlap, cotton and linen are on sale.

There is an inclination to apply a sense of responsibility—never more than two or three hours consecutively, in between these hot summer bike rides and ice cream, every day from Moabit to Wedding with public radio announcements, anachronistic propaganda formats, avoiding dumb European roaming costs on a smart phone, the return of the 30-minutes news cycle.

Sunbathing in ambivalent anarchy, those colors, a Swiss make, are inadequate. Those joyful, jolly colors, are colorant tools after all, a smeared state of affairs. The effect of potential and abstraction lies somewhere far beyond these picture planes, somewhere behind the sun.

This exhibition sums up a collection of events, one summer, one year, a European competition. Flags on the moon. Flags everywhere. How do the news relate? Various incoming reports on the results from multiple parallel worlds. It’s a thoughtless way to work, nothing elaborate, a plain depiction, and a more permeable way to perform that Lee Lozano-thing, an already made call-back to an older work;

fresh, runny water, this waste & hope, stuck up and in the sticks.

How to mix what you see at acrylic speed? Flags, rainbow colors and a fresh hammer-and-sickle graffiti somewhere on a fenced playground. That’s manageable, and perhaps surprisingly contemporary because this is the present, partly. That is the whole range of our present.

This exhibition attempts to delineate the world with oversimplified technique, incorporating a crass inadequacy, which, in its life-size model form, purports both fallacy and sovereignty through a hot pile of assumptions, quotes, allegations, proposals, shared understandings, misconstructions, comparisons, intrusions, and other fantasies, which fail to neither ratify nor deny what’s really what.

Recently, Kaspar Müller exhibited old books, bicycles and big words in different exhibitions. There might be enough time to let these ideas dry overnight.

Too Much Data

by Tenzing Barshee

Installation view, jmseradzfghdsjkfhbycmxcfnbkladshj, Société, Berlin, 2016

Installation view, jmseradzfghdsjkfhbycmxcfnbkladshj, Société, Berlin, 2016

Installation view, jmseradzfghdsjkfhbycmxcfnbkladshj, Société, Berlin, 2016

Frankfurt Freakout

Museum im Bellpark, Kriens, 2015

Kaspar Müller

One way to start thinking about this show would be with art-theoretical terms, hitting all the points about this place, this museum, bringing in these objects, talking about these patina covered ideas and concepts of post-readymade and appropriation. Another way would be just talking about the objects themselves, which would be, like Georges Perec writes about them in his book Les Choses, also talking about the relationship they have with us as a collective and with you as a person, or in society, defining classes, or distinction and the judgement of taste.

Peter Fischli

It offers different starting points at once. I like to see this moment, where one is confronted with reacting to this situation of parallel and overlapping, as a déjà-vu-like moment. I was always wondering if a déjà-vu can be somehow stimulated, maybe in art terms, maybe neurologically supervised, with calculated inputs of all senses. A déjà-vu is mainly a cerebrospinal “hang-up,” to use a computer term. The brain is not following up with processing the given information, even though it’s not a problem of understanding, but of processing. So it seems you have already been there, in the same dispositions. You can’t put it in order and you are haunted. But obviously in this show, besides the ones you mention, there is another important string, the media one, or say the “digitalization,” by which I mean on an obvious level: the books and CDs, and on a second level, also the furniture, that are part of an advanced digitalization. The designs, shapes and materials of what we see here, are already stored in the computer as files. The new furniture is almost completely plotted out from the files, using ingredients, and of course the licensed remakes of the old classics, which are digitally imported and adapted in a fully automated process. Of course not all of these objects were files when they were produced in their time, the Thonet rocking chair in the other room is over 100-years old, it was a drawing-board file then, which is now digitalized. What we see here is somehow this promise of complete digitalization and how it’s already become a reality, or how it’s shifting towards that. Though everything here is extremely tangible, its “origin” seems now shifted to the digital already.

KM

Yes. I mean, this also becomes clear on the second floor where you have this table with CDs. You never know if they are used or empty. On the mirrored side of the CD you can see your wondering face, asking the question of what’s stored behind the mirror. For me this became kind of obvious in this object. There is a nice contradiction in the problem that you talk about now: in the end, you could say that the books and CDs are places where information is stored, or a story is told, but still they are objects, so it’s the contrary with the furniture, which are objects “carrying” a file.

PF

That’s true. The furniture is a tangible object, created from a file, an item of use, a negative of the physical body—at least in European design. I have chosen very well-known and familiar pieces of furniture, which have, in common sense, become signs. For example, an actual Eames chair is already the sign for an Eames chair. What I mean is, when you look at the Eames chair, it’s not the specific material that you see first, it’s the sign it stands for and this dematerializes the furniture already. And then in the next step when you take the sign to a file of virtual numbers, it’s even less material than the sign. It’s gone and its envelope is left over.

KM

I would like also to talk about the topic of “having” or owning things, espe- cially furniture with their volumes and presence in our everyday life in contrast to just observing them here in a museum, and what it means to just own a file, a file of a book, a piece of music or a movie. Is owning a file a new form of “having”?

PF

If we think about software or a data carrier, we think about something unseizable, we think about the disappearance of the objects, this feeling of depletion. If you mention the different files, a book, a 16mm role, a stick with music on it, it’s like when you first heard a CD after the LPs, the lack of the swoosh was disturbing, instead it was like hearing the digital void.

KM

Schätze der Erinnerung

Société, Berlin 2014

Installation view, Schätze der Erinnerung, Société, Berlin, 2015

Installation view, Schätze der Erinnerung, Société, Berlin, 2015

Installation view, Schätze der Erinnerung, Société, Berlin, 2015

Installation view, Schätze der Erinnerung, Société, Berlin, 2015

John Beeson

Hey, Kaspar. So, to get started, should we talk about travel or about circulation?

Kaspar Müller

When it comes to these images of Lake Zürich, it’s mainly a matter of place. A very specific place. When you see the images, you won’t be in the same place, because they were all taken in Zürich, and the exhibition of the photos is in Berlin. So you would have to travel, even just in your imagination, to a specific destination. It’s not that much about traveling in general, but about one place, which might include traveling as a way of getting there—but then, that place has in a way traveled to Berlin. The lake is portrayed in a number photographs, unique moments captured over a year, over 4 seasons, in different weather conditions. What might follow could be called traveling, maybe, on a metaphoric level at least. Like memories don’t arise until they’ve been reflected by something, mostly something superficial, like a texture, a picture, a sound, an object, or a scent. I want to use the lake and the pictures first of all as a vehicle. Whether something breaks or reflects on it or just runs into emptiness and oblivion. At first glance, these works have a potential that could be compared to that of postcards.

JB

Could you say something about these photos, which you’re calling The Weather in Zürich—in relation to the works you’ve done in the past about a hat?

KM

I’ve done three projects with the hat: It started as a costume for an actor in my film about a specific place, or rather two places, edited together into one ideal place: Colmar & Strasbourg. There’s a strong parallel to the idea of the mise-en-scène of an existing place, to use it as a ready-made stage, not just with the facades but also to avail oneself of its “image” and reputation—though the lake is an “empty” stage, a stage for the landscape first and foremost. In my photos of Lake Zürich, there is no narrator, no guide measuring and mediating the place, like there is with the actor in the film Colmar & Strasbourg.

The protagonist is the lake itself. Also, the photos are static, captured moments, nothing moves. In the film, motion is very important—not just as the medium, but also the very slow flow of the actor (with the hat) on the ships trough the canals of Colmar and of Strasbourg, passing by the facades of buildings. Lake Zürich seems immobile, heavy. The rivers in Colmar and Strasbourg never stay put, the water passes into the sea somewhere in Holland. Lake Zürich is a basin, it stands still. The actor was wandering through places of conserved and mediated memories and historicized education, instructed by audio-guides, through a self-inflicted and vain mock Atlantis, lost in debates and self-portrayal, feeding from the past, almost like a facade built after its own cliché. It’s also a different way to recollect something when it’s mediated. The big, eye-catching hat had its origin in a promotional hat from Heineken, which I re-tailored with different fabrics. It made the actor look like a drop-out magician hippie lost in a touristy stage of colorful trippy half-timbered facades. The actor was constantly walking, or the ships were moving, so there was never a still moment.

While the touristic facades in Colmar and Strasbourg look damned, rotten, a civilization falling apart, almost without any nature, the lake looks like a utopian place, a treasure island, a safe heaven where nature and civilization have developed a symbiotic relation. The trees on the hills around the lake in Zürich have been cultivated so that one can’t see beyond the city, can’t see the rest of the world behind the green edges. A cultivated utopia. Zürich is a very strong and powerful place and, compared to many of the other places I’ve been, it still seems like an exotic place.

The lake is so clean, it’s actually classified as drinking water. The lake also has a symbolic value, of course, a basin contains things under its reflecting surface that can’t be seen. Which is also a fact. It’s like a mirror in which you search for deeper things, but you just reflect yourself. In this case, the whole landscape/sky is reflected. As for the images, they’re often divided by a horizontal line, almost mirroring that scene.

JB

Hm … reflecting, mirror, reflect, reflected, mirroring … Even if that mirrored surface is impenetrable, what might people read into the simple fact of it?

KM

As you say, one will want to read something into it, force it even, because it’s not acceptable for it to stop there, like with the image of a postcard that I mentioned before. Also, these images seem so very known from the point of view of a collective memory. Only very hard-boiled reception would leave it there. And I could only imagine Kleist or Poe finishing a story that would conclude with the simple fact of a reflection, and even then it would feed from the disappointment and tragedy because more was expected. Actually, I’m not averse to this. But before I come back to the mirroring, I want to mention the weather, which is very important for the images, also given the fact that it’s reflected on the surface of the water. The weather is a very strong influence on the atmosphere and the ambience, and it expresses that on the lake in particular. I paid a lot of attention to the weather. In the time I took the pictures, I captured very different weather conditions. Almost like in the German Romantic period, landscape and weather are inseparable. And it can bring out memories and thoughts with a bit of help from drama.

But one might assume there must be a dark potential. Or a twin potential. That there must be another side. If not, the rejection of any depth would almost amount to aggression. Whenever one talks about Switzerland’s dark side, that’s when its landscape shines the brightest. It seems almost to express it in that way because it demands an equilibrium. I just read a text from Jean-Luc Godard about the Swiss landscape. He says that as the Swiss people have internalized the disreputable character of their country in relation to certain issues from the past and present, that has been turned outside again. It’s the law of the équilibre. The landscape is there to clean that debt, and Godard assumes that Swiss artists and filmmakers always see and portray the landscape with a bad conscience. He of course films it, though, because it’s beautiful.

JB

What kinds of changes do you think occur when you combine images in the form of a grid (even if it’s just two images, or an uneven grid)?

KM

It’s definitely an uneven grid. These are handmade, rough collages. I mounted the photos on sheets of cardboard that I painted with wall paint first. With all these horizontal lines from the lake, it’s almost like adding up, stacking up. Normally, when you bring two images together, it’s a confrontation, which can lead to harmony or conflict. But because the horizontal line is so strong and there are so many photos of the same topic, I think the gesture leads more to an addition than to a confrontation. When you look up images of Lake Zürich on the Internet, you’ll find many pictures that look similar. So I’ve added my photos to a huge amount of already existing photos of the lake. They build first and foremost a visual collective memory. Be it from flickr, Google, social media or printed magazines. So with these images, it also begins to add up. We can only guess how the collective memory of an actual visit in Zürich could be like. And I wonder how diverse that would be. I always liked the idea of using lists (making lists) as a means of comparing things. A list, at least as long as it doesn’t have a purpose, is always complete, whether one takes something out or adds something. With the grid and the amount of photos spread in the space, the focus in the comparison lies more in the differences than in the similarities. But after a certain number of pictures of the lake – after yet another image – the viewer probably begins to feel indifferent about it. I want to push the images and, through that, to push the place into a beautiful redundancy and oblivion. So, the dark side could be oblivion.

Installation view, I Shrunk the Kids, Kunsthalle Bern, 2013, Photo: Gunnar Meier

F. Stroun and T. Barshee

What’s with the naked women flashing their breasts painted in the style of British artist Julian Opie at the entrance? It’s quite an aggressive way of greeting visitors to the Kunsthalle. How do you expect us to look at them?

Kaspar Müller

They aren’t just ‚in the style’ of Julian Opie, these are his actual motifs, which I’ve digitized from reproductions, cropped, and silkscreened on canvas before sticking a few diamonds to their surface. What interests me in Julian Opie’s pictorial language is that it is as ubiquitous as it is explicit. They are pictograms; the ,before-and-after’ woman flashing her breast looks like an airport security animation. Their explicitness is proportionate to their degree of abstraction: flat primary colors, an unvarying black outline, etc.

FT

You are not really suggesting that we should look at them as pure abstractions, are you?

KM

Of course not, that would be impossible. These images are problematic on so many levels. Some pay their dues to famous art history nudes. For example, the woman on the blue background clearly brings to mind Marcel Duchamp’s famous Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. But what makes these images disturbing cannot be reduced to their sexual subject alone. What‘s brutal is the way this abstract black line simultaneously neutralizes and amplifies their content. The effect is so evident, so brash…

FT

Are you talking about Julian Opie’s work or yours?

KM

Well, mine of course. I believe my process of appropriation and customization has not dimmed the iconic intensity of Opie‘s original pictures. These works – and the whole exhibition – attempt to negotiate an impossible truce between abstraction and representation. With abstraction comes language and knowledge. With figurative representation comes empathy, desire, rejection. Between these two points, a lot of room is left for interpretation and misunderstandings.

FT

Do you see yourself as a satirist? What function, if any, do you ascribe to the deadpan humor that permeates your work?

KM

The humor is basically mechanical: it’s the laughter provoked by watching something break down. I’m interested in heightening the failures that are intrinsically part of any system of representation. There is an implicit absurdity in the positions artists assume to make up for these malfunctions. It’s like watching someone slip and pretending nothing happened.

FT

Some may see this program of disenchantment as cynical.

KM

It’s just the opposite. There is nothing more cynical than to see people in front of magic tricks and falling for it. Humor needs to be a bit mean to be funny. Life is full of situations ripe for mean humor: compulsive repetitions, failures, unfulfilled desires, misunderstandings, etc. I think that for a lot of people, the experience of disillusionment is mistakenly perceived as cynicism. I find there is a particular beauty to it.

Corrective Detention

Société, Berlin 2011

Installation view, Corrective Detention, Société, Berlin, 2011

Installation view, Corrective Detention, Société, Berlin, 2011

Installation view, Corrective Detention, Société, Berlin, 2011

Installation view, Corrective Detention, Société, Berlin, 2011

Installation view, Corrective Detention, Société, Berlin, 2011

Kaspar Müller

Solo exhibitions

-

2023

Longevity, The Green Gallery, Milwaukee

Fünf Figuren, Société, Berlin

Liquid Artist, Atelier Amden, Amden

8 Figuren, Art Basel Parcours, Münsterplatz, Basel

-

2022

Maintenance 2, Galleria Federico Vavassori, Milan

Pentimento, with Golnaz Hosseini, Die Treppe/ Jan Kiefer, Birsfelden

-

2021

ANGEL, NICO, Bari

Corrective Detention, Aguirre, Zona Maco Art Week 2021, Mexico City

-

2020

In and Out, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich

Mandala, Société, Berlin

-

2019

Why always me?, Société, Berlin

Rendering of service in the pitch of the bruise, der TANK, Institut Kunst HGK FHNW, Basel

Allegiance and Oblivion, Vleeshal, Middelburg

-

2018

The Weather in Zürich, Aguirre, Mexico City

The Downer, Berlin

miart 2018, under the auspices of Federico Vavassori, Milan

Warum warum ist die Katze krumm?, with Margaux Dewarrat, Alienze, Lausanne

-

2017

Maintenance, Galeria Federico Vavassori, Milan

Presentation with Tina Braegger, Shanaynay, Paris Internationale, Paris

-

2016

jmseradzfghdsjkfhbycmxcfnbkladshj, Société, Berlin

Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich

Max Frisch Bad, with Cyrill Schläpfer, Zurich

Books, The Green Gallery, Milwaukee

-

2015

Frankfurt Freakout, Museum im Bellpark, Kriens

-

2014

Schätze der Erinnerung, Société, Berlin

Allegiance and Oblivion, Federico Vavassori, Milan

-

2013

I shrunk the Kids, Kunsthalle Bern, Bern

Forever Alone and Around the World, Kunsthalle Zurich, Zurich

talktalktalk (with Tobias Madison), The Green Gallery, Milwaukee

-

2012

Zu Weihnachten (with Roman Signer), Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich

Stand-Up, Gasconade, Milan -

2011

I was in Trinidad and learned a lot, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich

Corrective Detention, Société, Berlin

Kaspar Müller, Curated by Roman Kurzmeyer, Atelier Amden, Amden

Circuit (with Emil Michael Klein), Centre d’Art Contemporain, Lausanne

-

2010

Manorpreis Schaffhausen, Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen

-

2009

Muster, Paloma Presents, Zurich

Bias, Kunsthaus Baselland, Basel

Don‘t Support the Team, Galerie Nico, Basel

-

2008

Permanent Vacation, Vrits, Basel

-

2006

Service, Vrits, Basel

Ich&Du Wir&Sie, Schalter, Basel

Group exhibitions

-

2023

SHINE ON, Sadie Coles HQ, London

Hoi Köln, Teil 2: Im Bauch der Maschine, Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne

Hoi Köln, Teil 1: Begrüßung des Raumes, Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne

Nicolas Krupp, groupshow curated by Kaspar Müller, Basel

The Poet’s Folly and the Sovereign’s Hand, Wehrmühle, Biesenthal

Shōkakkō, The Merode, curated by Emmanuelle Indekeu, Brussels

Es ist Herbst, wir fallen, Various Others, Munich

The Northern Renaissance Fair, Berlin

Basel Social Club, Basel

-

2022

Watercolours, Chapter II, Weiss Falk, Zurich

Pentimento, Die Treppe, Basel

-

2021

Più Luce – Mehr Licht, Casa Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno

Stop Painting, Fondazione Prada, Venice

Signatures, Smallville, Lausanne

-

2020

MPP, MÊME PAS PEUR, Martina Simeti, curated by Davide Stucchi, Milan

One Moment Please, Triest, New YorkA Stately Interior, Aguirre, Mexico City, Mexico

After Bob Ross Beauty Is Everywhere, Museum im Bellpark, Kriens

KASTEN, Stadtgalerie, Bernall clothes artists’ own, Galerie Gregor Staiger, Milan

Ride off like a cowboy into your sunset, Aguirre, Mexico City

-

22019019

Die Läden sind geschlossen, Weiss Falk, Basel

The Clockwork, The Performance Agency at Paris Internationale, Paris

SELBSTBILDNIS, Société, Berlin

Absolute Thresholds, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich

Le ciel, l’eau, les dauphins, la vierge, les flics, le sang des nobles, l’ONU, l’Europe, les casques bleus, Facebook, Twitter, Forde, Geneva

Prix Mobilière 2019, artgenève, Geneva

A chair, projected, Bolte Lang, Zurich

10 Years of Provence, The Downer, BerlinHidden Bar, Art Basel, Basel

-

2018

20 Jahre Kunst Raum Riehen – Die Jubiläumsausstellung, Kunst Raum Riehen, Riehen

Ready Made 2, Swiss Institute, New York

The Performance Agency “Mass X (The Unfolding)”, Supportico Lopez, Berlin

‘haha‘‘, Aguirree, Mexico City

The emotional Content of the Revolution, Wesminster Waste, LondonTeam 404, Zabriskie, Geneva

-

2017

Über ein Glas Wein, 67 Steps, Los Angeles

FROM BERLIN WITH LOVE, Istituto Svizzero di Rom, Rome

Beauty and Room, Stadt Zürich Kultur, Zurich

Zeitgeist 2, MAMCO, Geneva

Salon Vogue, New Bretagne Belle Air, Essen

-

2016

Sculpture Quadrennial 2016, MMIC, Riga

The Hellstorm Chronicle, Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin

-

2015

Stipendium Vordemberge-Gildewart, Biel

The Grand Reception, Aachener Kunstverein, Aachen

Groupshow, Part I, Cologne

The Longest Bridge, Off Vendome, New York

A Form is a Social Gatherer, Plymouth Rock, Zurich

Nimm´s Mal Easy, Ausstellungsraum Klingental, Basel

-

2014

Postcodes: Kind, Organized by Gabriel Lima and Pedro Wirz, Espaço Coletor, Sao Paulo

Europe, Europe, Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo

BAK Swiss Art Awards, Basel

Truth and Consequences, Pocari Sweats, Geneva

The St. Petersburg Paradox, Swiss Institute, New York -

2013

X-MAS, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich

Trust (A mi izquerda), Curated by Michele D`Aurizio, Galerie Balice Hertling, Paris

Log-O-Rithmic, GAMEC, Bergamo -

2012

La Demeure Joyeuse II, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich

D‘après Giorgio de Chirico, Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, Rome

Accardi (with Emil Michael Klein), Federico Vavassori, Milan

La jeunesse est un art, Jubiläum Manor Kunstpreis 2012, Argauer Kunsthaus, Aarau

Shake & Bake, Galerie Praz-Delavallande, Paris

A Strangely Luminous Bubble, Haute École d’Art et de Design, Geneva -

2011

Corrective Detention, Société, Berlin

Dressing the Monument (with Tobias Madison), Lynden Sculpture Garden, Milwaukee

Glee, Curated by Cecilia Alemai, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles

Groupshow, Karma International, ZurichCorso Multisala & TCCA, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen

-

2010

Belle-Idée #3 (with Damian Navarro), Espace Abraham Joly, Geneva

Do it to Do it (with Tobias Madison), Kunstverein München, Munich

Suppose this is true after all? What then? (with Tobias Madison), Johan Berggen Gallery, Malmö

On Publications, Portraits, Public Art and Performance, The Modern Institute, Glasgow

Of Objects, Fields, and Mirrors, Kunsthaus Glarus, Glarus

Quick Brown Fox & Lazy Dog, Karma International, Zurich

-

2009

Tbilisi6, Curated by Daniel Baumann, Nana Kipiani and Ei Arakawa, Tbilisi

The Forgotten Bar Project, Galerie im Regierungsviertel, Berlin

P. Arabian Horses, Layr-Wuestenhagen Contemporary, Vienna

The Line is a lonely Hunter: Drawings in New Jerseyy, New Jerseyy, Basel

Preview Dinner, New Jerseyy, Basel

Showroom 1: Q, Basel