Petra Cortright

Art Basel Parcours 2023 Petra Cortright

June 15 – 18, 2023

Reckless Bloom: On Petra Cortright’s Shuddering Landscapes

Kate Brown

It is said that a significant marker of climate apocalypse will be madness pervading the seasons, a kind of riptide devouring natural logic and shifting the lengths of the meteorological calendar. In her new video work, American artist Petra Cortright’s pastiched landscapes defy the assumed order of ecosystems, conveying a low-level anxiety that one might feel when the weather stops making sense. But her crafted scenes also come with a sense of relief. The piece, called

green hill green light esprit de corps, is laced with optimism and freedom.

As is well-evidenced in her ongoing art practice, Cortright is invested in the history of painting. Her scenes recall a continuity of painters throughout history who have tackled nature as subject matter and our own fragility in its grip. To beat back against this notion, painters interpreted the natural with touches of surrealism as Cortright does here. Think of Caspar David Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice from 1823, a work edging on the surreal so much so that it confounded audiences at the time. That kind of Romantic feeling swirls through the artist’s filmed landscape.

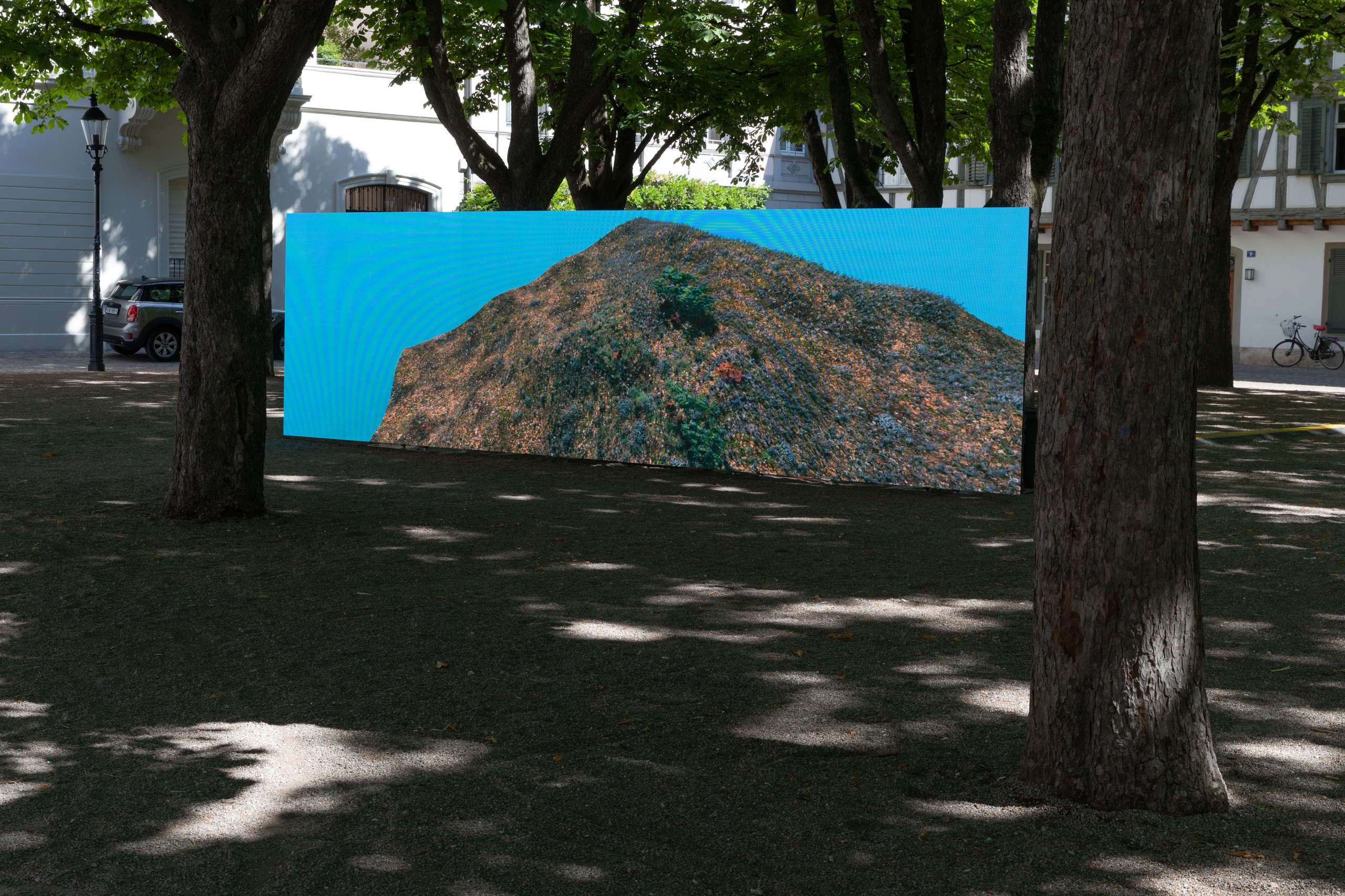

This cannot be real, not for a moment. When writing about modernist painting, art critic Clement Greenberg described how the Impressionists left “the eye under no doubt as to the fact that the colours used were made of real paint that came from pots and tubes.”* Similarly, Cortright leaves digital details out in the open for us. Low-res grittiness recalls that her pot and tube is a Wacom tablet and downloaded digital brush sets. And that “utter flatness” of modernist traditions that Greenberg croons about is embraced too, via FlowScape and Photoshop. Cortight’s hand is obviously present, meandering, searching, and testing boundaries across bucolic scenery. But is it a creator or a witness? This question haunts the video as we gaze at the blank undersides of daisies catching lens flares.

Disparate foliage is yoked together: we meet a ground of dead leaves but there are no trees from which they fell. The forest floor is like a desktop background, a kind of catchment basin for things nature shrugs off. And it gets wiped out sooner or later, subsumed under the surface and into the bin of earth underneath. The decaying leaves are cut against a bright sky, and they shift under cloud shadows. The limitlessness of the blue is dizzying and this delicate patch of earth teeters between states of birth and nonexistence. Exotic shells bloom in ashy earth. Daisies and cornflowers explode from a rootless, untethered surface.

Cortright’s flowers have a noted stillness even when they pop up from the thin pixel relief. This begs another question: Are we looking at landscape painting or something more akin to still life? I am thinking of what the influential American art historian Norman Bryson noted about Dutch still life painting in particular, a movement that brought together nature from all corners of the world into the space of single paintings. In these works, few connections between the natural objects presented existed. Bryson notes this, adding that “when the framework of space and time is effectively neutralised, there is an elevation of human powers over creatural limitation.” In such paintings, he notes, “lurks a certain Faustian ambition.” * Empty shells from different oceans collapse distance, and flowers from far-off lands result in, as he puts it, the “abolition of place.”

This kind of power taken up by artists was exciting and provocative then as it is now, but we have different tools. Pioneering artists working in the 16th century could not have imagined how flat and stacked the pictorial world would become as it does in Cortrights’s depicted terrain.n

As an artist based in the American West, Cortright has, by osmosis, inherited awareness of distressed ecosystems. The pictorial plane of green hill green light esprit du corps borrows from land-use studies, those diagrams that show controlled flows of water, which map out a controlled forest burn in an attempt to fend off a real one. In such illustrations, multiple scenarios play out at once. And similarly, in Cortright’s 17-minute film, the viewer witnesses a perplexing conundrum of scenarios: cumulus clouds hang above the sun-filled ground and it is also drizzling and it is simultaneously storming. Everything is growing, degrading, and regenerating. A closed loop.

What can we understand from our scientific, artistic, and technological attempts to get to know nature? On some level, pursuits of making sense of things have always been pretty futile. Nothing is inherently important, it’s all about vibe. We have always been at the whim of the world. And so, the artist searches for meaning, or at least beauty, in their work. In Cortright’s case, the hunt is across a delicately rendered map, though it may be better understood as a mind map. The artist searches, maybe, for something like spring. Soon we are panning away from this mirage-like landscape—our anxiety ebbing and flowing as we try to rationalise an irrational place. One may hear the fading echo Rainer Maria Rilke, who captured most perfectly, that seasonal, desperate wonder of the world:

“Everything is blooming most recklessly; if it were voices instead of colours, there would be an unbelievable shrieking into the heart of the night.”

*Greenberg, Clement. “Modernist Painting.” (1965). Art in Theory 1990–2000, 2003. Edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood.

*Bryson, Norman. Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting, 1990. Reaktion Books.

green hill green light esprit de corps depicts a perpetually morphing, computer-generated landscape. Slow, infinitesimal movements populate an isolated hill with sprouting shrubs and flowers. This bucolic scene is relentlessly scanned by a roving digital eye tracking through the chaparral, leaves, and grasses from a worm’s-eye view. At once ethereal and unsettling, the composition represents a subtle reference to the devastated political and physical landscapes of the American West.

Petra Cortright (b. 1986, Santa Barbara) lives and works in Los Angeles. Cortright has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Doota Plaza, Seoul; LIMA, Amsterdam; UTA Artist Space, Los Angeles; University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh; and Depart Foundation, Los Angeles. She has also participated in numerous group exhibitions at international venues including the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; KM – Halle für Kunst & Medien, Graz; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Kunsthaus Langenthal, Langenthal; New Museum, New York; 12th Biennale de Lyon, Lyon; and SJ01 Biennial, San Jose.